PIRAS. Historias de brujas

TOTEM TABÚ

29.06.19 - 13.10.19 / Sala PAyS

Curator: Florencia Battiti

–

Of Witches and Covens

Collective resistance as an ethical-political practice

The witch is a figure that inspires fascination as well as terror. Do they exist? Do they have supernatural powers? Do they eat children? Do they heal sick people? Do they use brooms to travel? Are they old and grumpy? Young and beautiful? Sexually perverted? Completely asexual? Social failures? Are they evil or good? Are they heretic? Throughout history, we can find multiple tales about witches, diverse, even opposing speeches and of various styles: Disney films, TV shows, treaties that work as inquisition manuals, feminist claims, engravings, and paintings, for mentioning a few. There isn’t a single tale about witches and maybe that is the reason for its political power, that persistence of figurations that demand new writings and re-writings, especially since they contain, as Donna Haraway notes, some kind of displacement that may question certainties and problematic identifications (1). This way, every iteration is capable of establishing new meanings, disrupting the old, opening new semantic possibilities in the grammar of what has been given. Nowadays –in times of neoliberal governance, as Michel Foucault pointed out(2)-, what new inscriptions are applied to the figure of the witch or, we should say, the witches, perhaps the non-binary witches?

Whether it be the witch-hunt of early capitalism, functional to the establishment of a patriarchal order that establishes the figure of the witch around cis women who are “savage beings, mentally weak, insatiably lusty, rebellious, insubordinate, incapable of self-control(3)”, or all the figures originated from this point: the one who searches for eternal youth, the one who deals with the devil or destroys divinity, the one who lives in an isolated cave, the one who no one visits without some fear, what connect all these witches is, that in one way or another, they are in the margins of women’s expected roles and from there they challenge some aspect of the established order.

But the pejorative sense, the fear, is cracked with fascinations: feminist identifications that adopt witches as a symbol, twisting the fate of established figurations. From W.I.T.C.H (Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell) collective in the seventies in United States to the current popular singing “we are the granddaughters of the witches that you weren’t able to burn”, some feminists recognize themselves in the figure of the witch, but not unambiguously in the “good witch” or the “evil witch”, because what contemporary figurations are challenging is, precisely, the tablets of Good and Evil. And even though we don’t believe in legit descendants any more, creating a lineage fiction without a single ancestor allows us to be part of a collective history that started before us, creating bonds and social identities. Perhaps this plural (“we are the witches…”) refers to the collective as an ethical-political practice of resistance.

Feminist covens have been growing exponentially for a while. Assemblies, mobilizations, spaces of discussion, for mentioning a few, are plural and concerted gatherings(4), as Judith Butler described. Bodies and diverse subjectivities come together not for producing a Subject of resistance anymore (unique and “ontologically” predestined), but in order to find in the multiplicity a collective practice that could work as political resistance. Women, lesbians, transvestites, trans, bisexuals, non binary, fat, native, Afro-Argentines and black, employed and unemployed, salaried, workers of the popular economy, sex workers, migrants are part of a list constitutively incomplete and open (one of the virtues of feminism: the capacity of reviewing and transforming itself). Witches and not so much, with or without magic, gather here and now, a one-way political coven that is produced, performatively, in each occasion.

Malena Nijensohn

Dra. en Estudios de Género

_

1. Cfr. Donna Haraway, Testigo_Modesto@Segundo_Milenio. HombreHembra©_Conoce_Oncoratón®. Feminismo y tecnociencia. Barcelona: Editorial UOC, 2004.

2. Cfr. Michel Foucault, Nacimiento de la biopolítica. Curso en el Collège de France (1978-1979). Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2007.

3. Silvia Federici, Calibán y la bruja. Mujeres, cuerpo y acumulación originaria. Buenos Aires: Tinta Limón, 2010.

4. Cfr. Judith Butler, Cuerpos aliados y lucha política. Hacia una teoría performativa de la asamblea. Buenos Aires: Paidós, 2017.

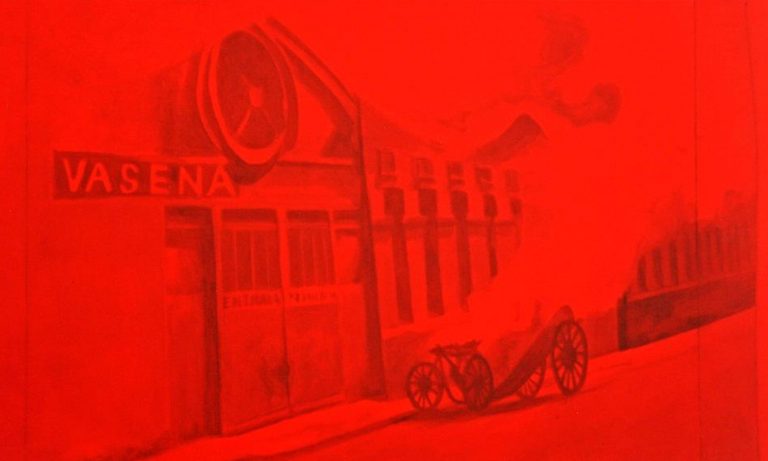

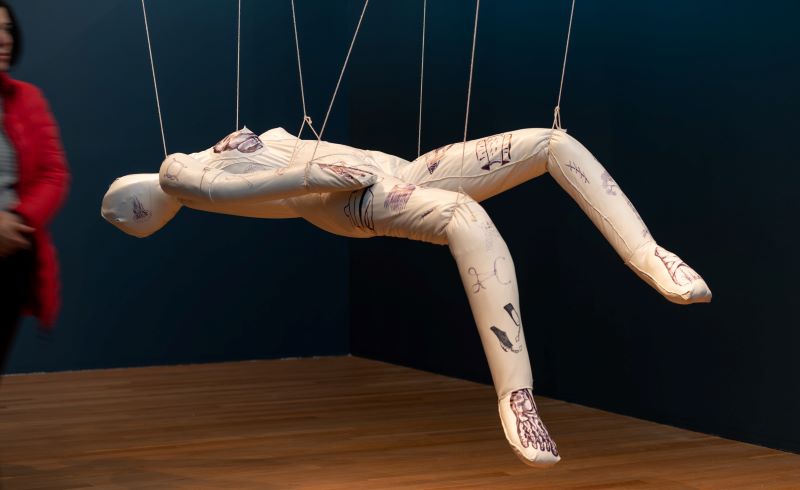

Totem Tabú, a group that consists of Laura Códega, Malena Pizani and Hernán Soriano, works since 2014 researching topics related to the origin of certain prohibitions. The group aims to shed light on the knowledge and ideologies censored by history and to observe how these have survived until the present day.

Press

¿Quiénes son las brujas contemporáneas?

by Ivana Romero

Página 12, 23/08/19

Historias de brujas y mujeres fuera de orden

by Laura Casanovas

Revista Ñ, Clarín, 13/08/19

Entre brujas, clásicos y geometría: una selección de cinco muestras de arte para disfrutar durante la semana

by Juan Batalla

Infobae, 15/07/19