LUCHA DE CALLES

Imágenes y Relatos a 50 años del Cordobazo

Collective exhibition

22.03.19 - 09.06.19 / Sala PAyS

Curators: María Alejandra Gatti – Cecilia Nisembaum

–

50 years after one of the most significant popular revolts in our history, the exhibition problematizes this historical event through the semantic potentialities provided by archival materials and the poetic possibilities allowed by contemporary art.

What is left today of the insurgent power of that revolt that brought together workers, students, and neighbors in the same complaint? What gestures and what forms shaped the rebellion before the oppressive weight of repression and the subjugation of the rights? How to recount this scheme without losing sight of the new meanings that emerge with the passage of time?

Along these lines, we revisited a milestone of recent Argentine history by connecting different documentary materials with works by Tomas Espina, Enrique Jezik, Hugo Aveta, Fernando Allievi, Lucas Di Pascuale, Julia Mench, RES and Marcelo Brodsky.

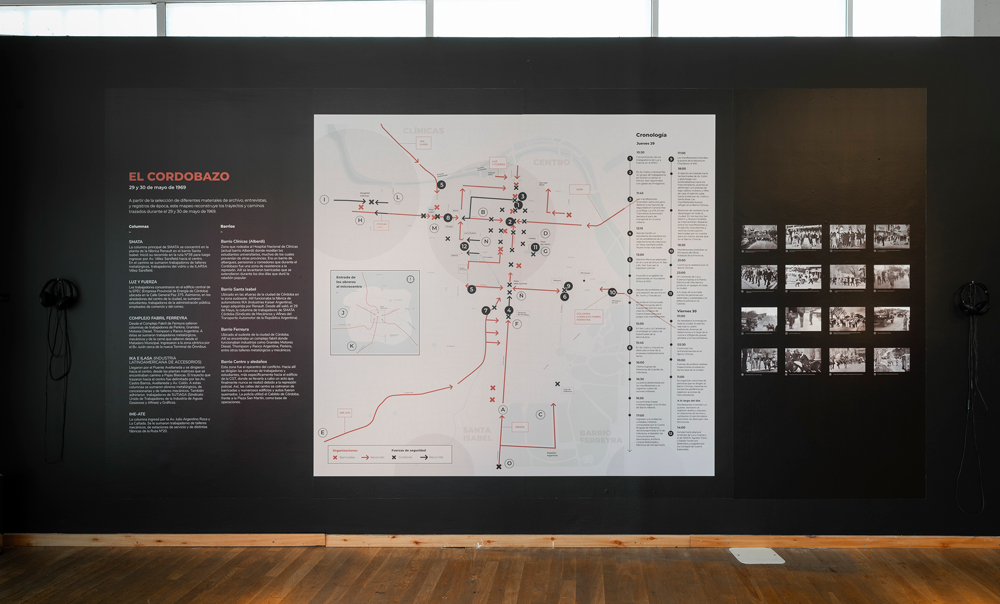

Paying attention to historical accuracy, and as a collective exercise, we start from some core ideas that allow us to sketch links and bring light to areas that, in a way, reshape that scenario as they bring it back to the present time, in a sort of palimpsest that provides new layers of meaning. Likewise, this exhibition reinforces the decision taken by Organismos de Derechos Humanos (Human Rights Organizations) of initiating the Monumento a las Victimas del Terrorismo de Estado (Monument to the Victims of State Terrorism) roll call in 1969, with the names of the victims of the Cordobazo and the posterior popular revolts that took place in other areas of the country.

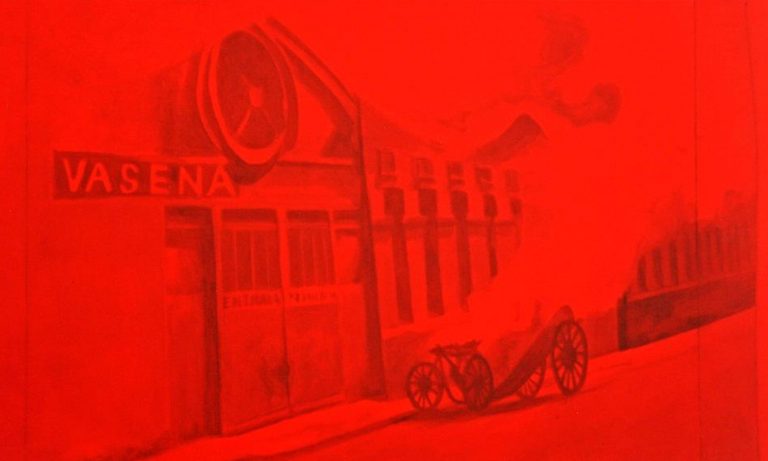

The Cordobazo remains in the Argentine political imaginary as an icon of popular rebellions. The events that took place on May 29 and 30 were portrayed by a vast number of photojournalists and camerapersons that were also witnesses. RES, as well as Allievi, appropriates these images not to certify the truth of the facts, but to unveil, by this action, new readings from our present time.

In the face of barricades and burning cars images, history builds a mythical epic around the peculiar conjunction of workers and students organizations. The works of Aveta and Espina oscillate in this dialectic between violent and heroic. Brodsky’s and Di Pascuale’s works are a counterpoint between what’s collective and what’s individual. Both, in different ways, allude to the international and local context, influenced by that political utopia.

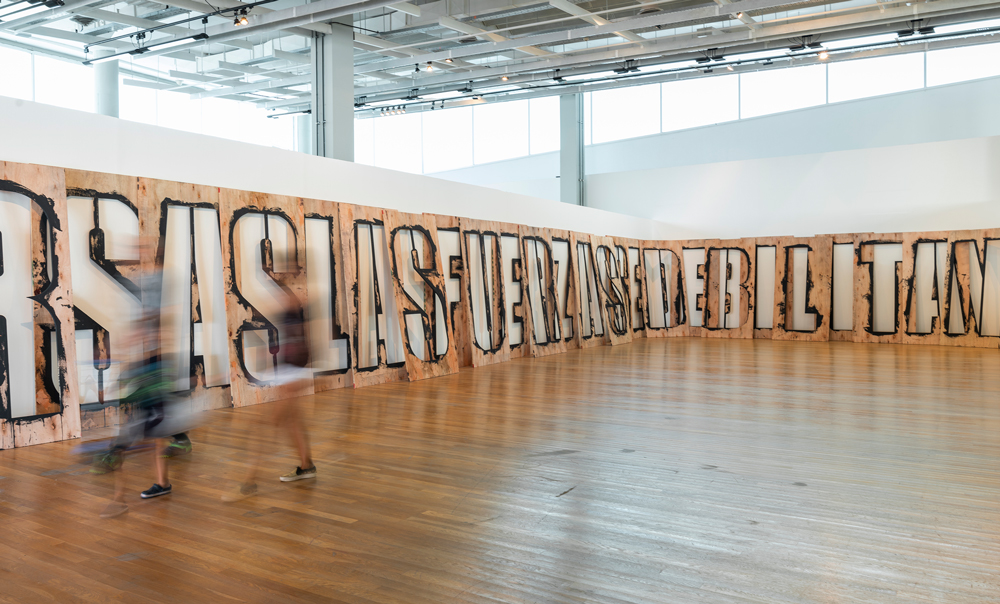

No historical event is stick to its origins; every time it is recalled, it is also updated, re-engraved in a new context. Thus, Mensch and Jezik works take phrases from different places and make them their own, recovering meanings that are updated outside the borders of their original context.

Facing the epic of the popular revolt –that remains in the memory as a landmark of collective resistance and participation– allows us to critically re-think our present, ask questions and articulate claims that may take shape and gain strength as a political act.

María Alejandra Gatti – Cecilia Nisembaum

A moment of victory

The protesters are in the middle of the street. The mounted police move towards them; they are charging ahead. A shower of stones and other projectiles welcomes them. So they stop and retreat. They will come back, but a moment of victory was filmed, a blow to Goliath. Those seconds, in low-quality black and white, became the canonic images of the Cordobazo.

The great revolt that started on May 29, 1969, is usually recalled as a people’s triumph. A date that might be claimed by many groups: different currents of the left, Peronism, segments of Unión Cívica Radical, “progressivism” –distant from the others–, unions, Catholic groups that suggest “an alternative for the poor”, and more. The massive demonstration against General Ongania’s dictatorship carried out by workers, students and other men and women from Ciudad de Córdoba –that was transformed, after the failure of the first repression, in a popular rebellion that briefly controlled the urban space– inspired and inspires affection.

There are many ways to approach the Cordobazo. If we analyze the circumstances, we can see it as the result of a general resistance to the economic adjustment, the authoritarianism of the “Revolución Argentina” –established through a military coup in June 1966–, and Cordoba’s particular circumstances. The labor movement was strong; the student movement especially active and the “Primer encuentro nacional de sacerdotes para el tercer mundo” (First Encounter of Priests for the Third World) had been celebrated the previous year. In 1969, the strike was encouraged by the growing discontent of metalworkers, autoworkers and Light and Energy and transport unions’ due to different reasons in each sector and because of the national policies. The conjunction of three union leaders initiated the Cordobazo: Elpidio Torres, Atilio López (Peronism) and Agustín Tosco (aligned with the left).

Broadening the geographical scale, we can notice various milestones that took place between 1968 and 1969: The French May, Vietnam War sit-in in the United States, The Prague Spring in the communist bloc and the Tlatelolco Massacre in Mexico. There also appeared massive protests in Montevideo, Rio de Janeiro, Santiago de Chile, Bogota, London, Milano, Rome, Belgrade, Dakar, Melbourne, among others. In this way, the Cordobazo was part of a series of important youth-led and sometimes worker-led protest movements that went beyond national borders. And if we take it further and we consider the temporal scale, Cordoba’s events are part of a tradition of popular participation that has been key in Argentine politics since the XIX Century.

The Cordobazo had relevant consequences. Even though the army recovered control over the city and the main leaders were incarcerated, the movement announced the failure of the dictatorship’s project to redefine the rules. Together with other revolts, other Argentinean “azos” between 1969 and 1972, it set the course of the popular resistance and it was the starting point of a political and social radicalization of great proportions.

Very soon, it became a legend. For the ones who experienced it, it was a model. For us that were born afterward, one of those moments with aura; when the reality is questioned, when the human action seems capable of anything. Even if it wasn’t without tragedy –the death of the worker Máximo Mena due to a police fire signified the first martyr–, and may be due to the vertiginous events of the following years, the Cordobazo remained to some extent separated from the posterior armed fight, from the spiral of violence and State Terrorism. It remained in its place before the fear, before the massacre; and in its wake endures a shinier memory.

A half-century is a long time. Little seems to be left in Cordoba of that Cordoba. Our Argentina is doubtlessly very different from the one of 1969. There will be many commemorations this year, and certainly, this contrast will be highlighted. But the Cordobazo isn’t only a moment of the past. It is a legend that is still relevant and will remain alive as a hope.

Gabriel Di Meglio

Artists

Fernando Allievi

Hugo Aveta

Marcelo Brodsky

Lucas Di Pascuale

Tomás Espina

Enrique Ježik

Julia Mensch

RES

Press

Una muestra sobre el Cordobazo se inaugurará en el Parque de la Memoria

Télam

16/03/19

Exposición sobre el Cordobazo

América Latina

22/03/19