ASSAIG S.T. 1909-1919

Gonzalo Elvira

15.11.19 - 17.02.20 / Espacio Base de Datos

Curator: María Alejandra Gatti

–

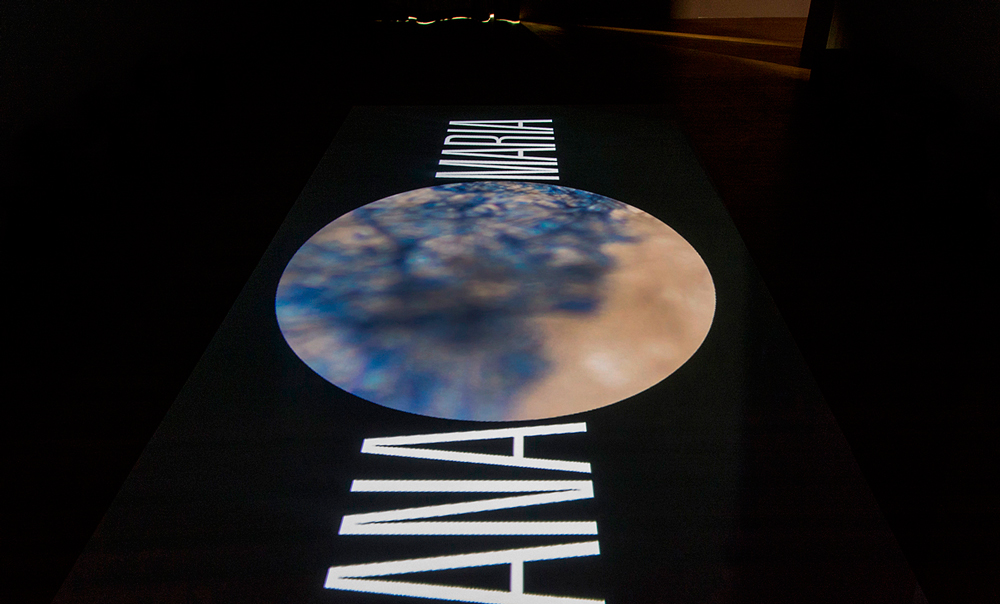

Assaig / Essay: Between Barcelona and Buenos Aires

“Whenever we are before the image, we are before time”, this is the first line of Didi Huberman’s famous essay that brings up the question about the meaning imposed by images on the relation between history and time. Images outlast people and, before them, the present reconfigures itself continuously, unfolding meanings that update their own frame. The anachronistic is the intrusion of a time inside another, the chronological and lineal irruption of facts, as a way of establishing non-continuous and heterogeneous paths that enable new readings.

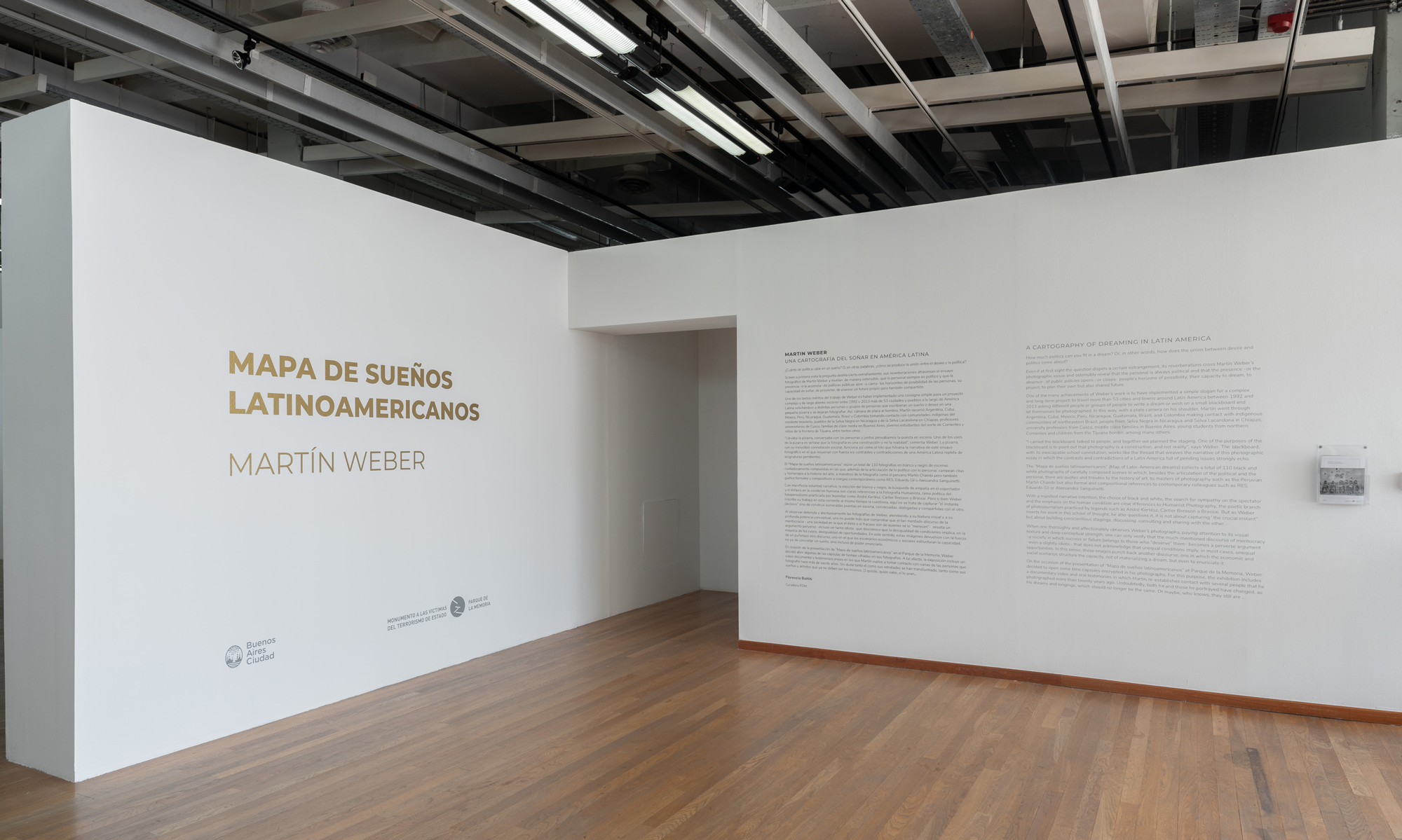

One hundreds years after the Semana Trágica de Buenos Aires (Buenos Aires’ Tragic Week), we present in Parque de la Memoria “Assaig S.T. 1909-1919” by Gonzalo Elvira, an Argentine artist based in Barcelona. The exhibition collects a group of works that intertwine, as an anachronistic exercise, the events during the “tragic weeks” that took place in Barcelona (1909) and Buenos Aires (1919), and brings to the present (2019) the possibility of questioning the political representation, social and economic crises experienced over these 100 years of history.

The events known as Semana Trágica de Barcelona (Barcelona’s Tragic Week) took place between 26th July and 2nd August, 1909. The decree of Antonio Maura’s government, aimed to send reserve troops to the Spanish colonies in Morocco, generated a series of protests against the war and the deployment of reservist soldiers, who mainly belong to the working class. After the protests were intensified, the unions called for a general strike that was followed by riots and a popular insurrection which resulted in fierce repression in the hands of Maura’s government, who declared a state of war and sent the army to the streets, leaving thousands of wounded and murder victims as well as prisoners.

During the week of 7th-14th January 1919, the also called Samana Trágica took place in Buenos Aires. After a long strike claiming for better labor conditions at Talleres Vasena, and after the murder of a worker in hands of strike-breakers groups, thousands of metallurgical workers declared a general strike. During thas week, the police, the army, and ultra-nationalist parapolice groups chased, incarcerated and tortured strikers and protesting residents.

Despite the geographical and temporal distance, both experiences were an organized rejection of a system that has historically imposed unequal conditions, always unfavorable to the working class.

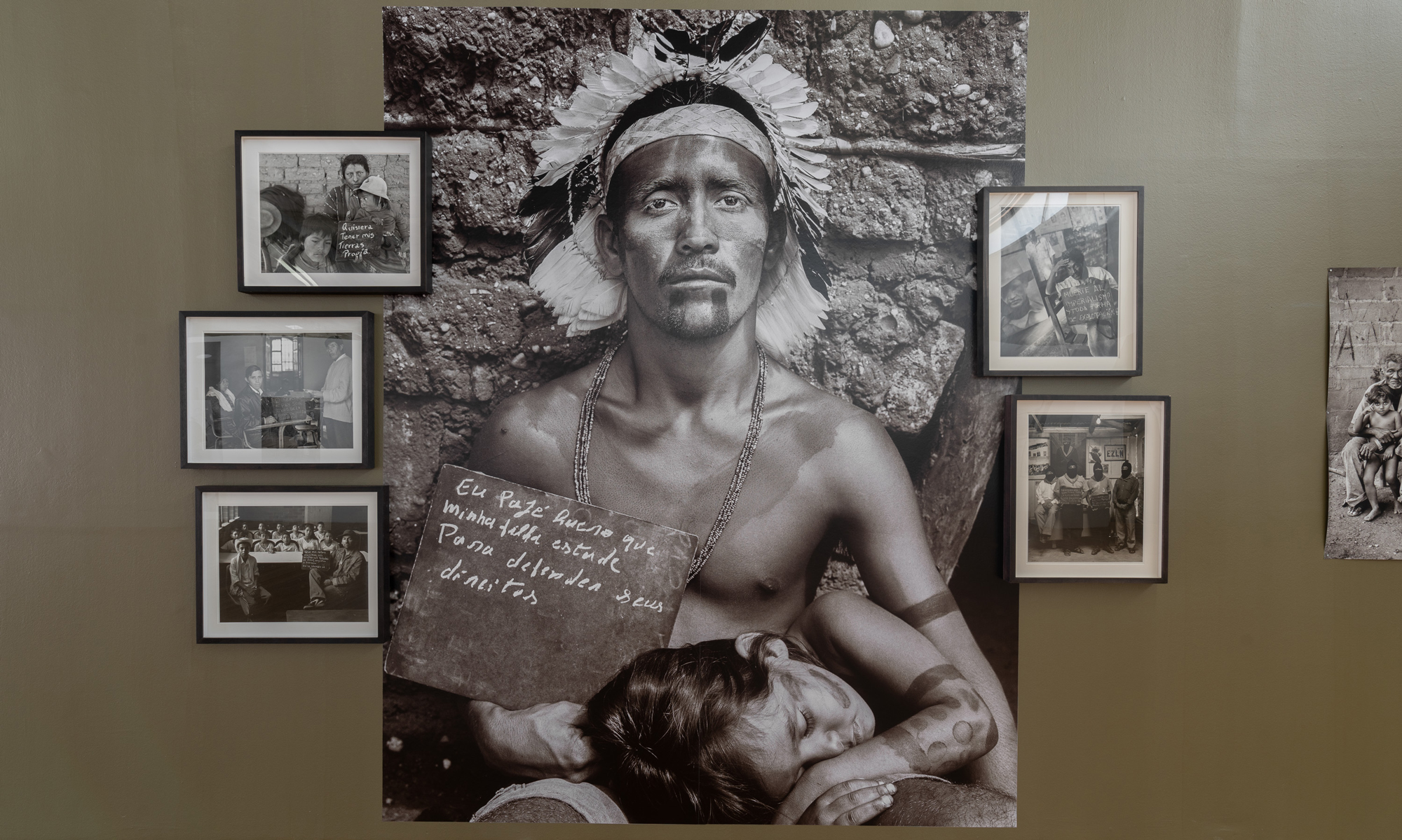

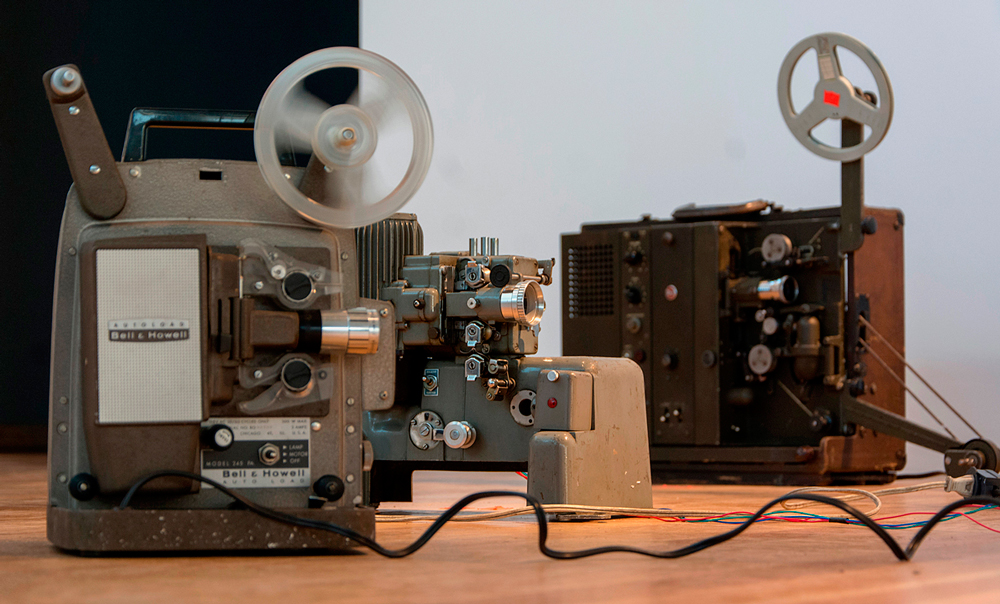

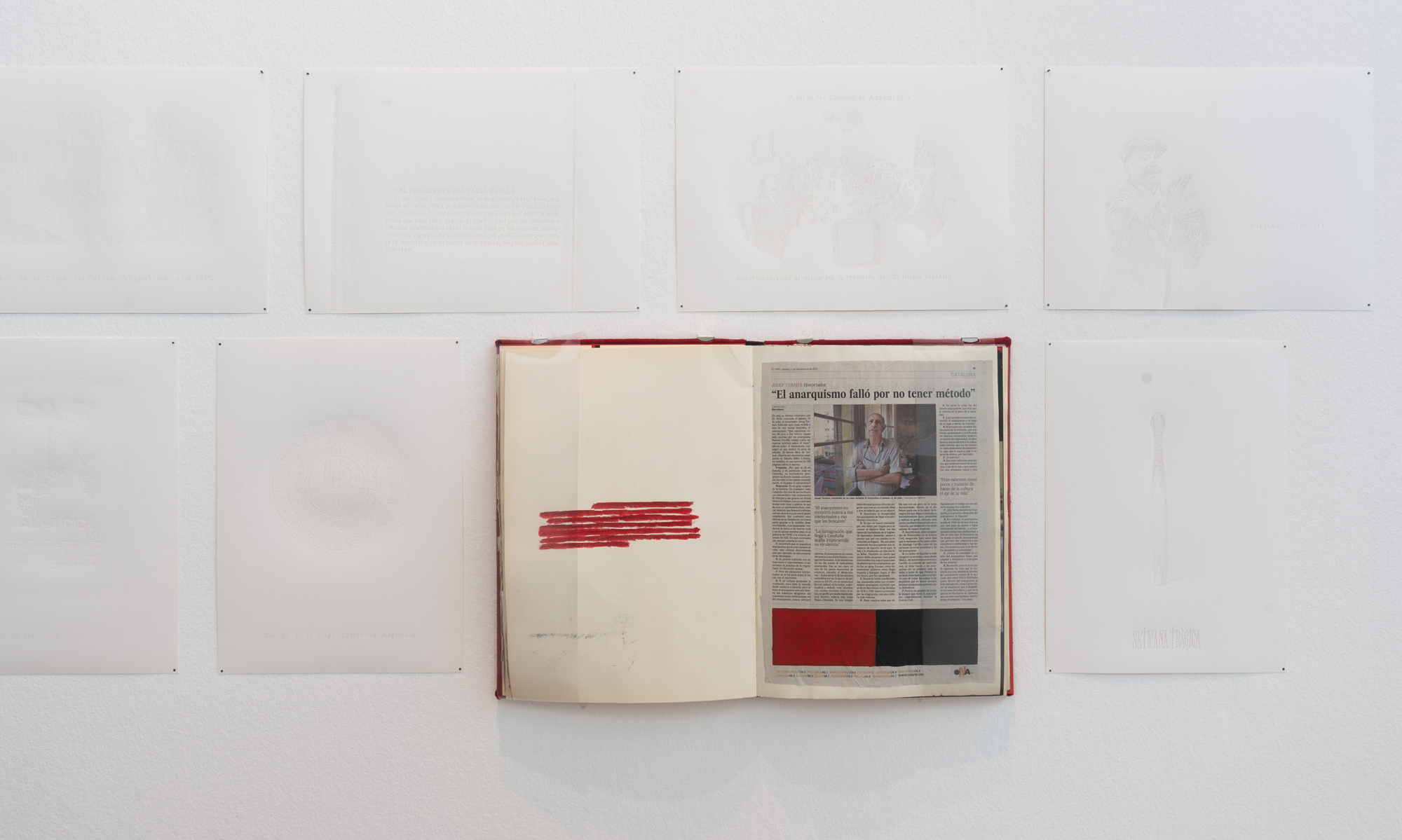

Based on a heap of documentary images, records of crowds on the streets, barricades, confrontations, street and corner postcards of both cities, Gonzalo Elvira intervenes the material sense of the images in an exercise that twists the logic of archives: photography, in this case, turns drawings and paintings into record material, and the oil paintings are displayed in glass cabinets as if they were documents.

In this operation that articulates the physical and conceptual planes, a series of portraits pierced by hammers and pins restores the ideological sense behind the historical overview. A technique that condenses one of the workers’ bond symbols, the puncture as a metaphor of the shooting and the violence and maybe the crisis of a system that outside its time repeats a pattern: the rejection of the legitimacy of liberal and neoliberal politics settled in each context.

Elvira presents an essay in which the image allows us to reflect about its state of atemporality, about its capacity of establishing meanings outside its time, and mostly about the possibility of universalizing the incompetence of a system that throughout history replicates the same logic.

María Alejandra Gatti

Curadora

About the Traceability of a Present Past, or How to Weigh History

1. Fiction

Considering a trace that could be merely biographical. The places one inhabits. There where what we call everyday life happens and there where the space of affection manifests. Or both, maybe. A story that moves between two cities in which, as well, the protagonist’s life happens. Buenos Aires and Barcelona.

We can’t omit that we are talking about ourselves, but maybe there is nothing further from our desires than doing so.

2. The trace

Two apparently unrelated stories but full of knots, a net that is woven between characters that are linked to one place and the other. Two events separated in time, in two distant places. Claims and subversion that are intertwined. History doubles, folds and lets us see the interstices, it lets us glimpse and formulates the other lights that appear behind great narratives.

Two spaces of revolt, a 10-year gap and many common knots that tell different stories, but happened.

3. The fold

Detailed images, patiently executed, from photographs of the real. Other realities emerged from the conscientious gesture of the hand, from the grimace of memory, the drive between what is said to have happened, what happened or what could have happened. What if in reality any revolt is woven by the others?

The drawing taken from the photograph, from the document, and faithfully reproduced as a whole, but elaborated through small lines or incisions that remind us the multiple narratives of each of the strokes.

Some time ago Gonzalo Elvira started a series about Semana Trágica de Barcelona (Tragic Week of Barcelona) (1909) and Semana Trágica de Buenos Aires (Tragic Week of Buenos Aires) (1919). A work of rewritings that raises questions around the project of modernity: its places, events, ideas, and main figures. A task that details narratives and uses drawing as a political gesture itself, which becomes a process of erasing the real image to recreate a faithful replica that, by its very essence, alters the image upon which is based. In this work, History is dismembered, as drawing does, in small strokes, and reveals the micro-histories that are linked by configuring other stories. Wouldn’t it be possible to follow the strokes of the song? Perhaps a songbook is suggested here, a collection of gestures that not only aim to reach stories but also to pierce our gaze. Let’s let the fiction, the trace, and the fold act. And let each one write their own possible coda.

Teresa Grandas

Gonzalo Elvira

Gonzalo Elvira (Patagonia, Argentina, 1971). He studied at the Escuela de Artes Visuales Antonio Berni in Buenos Aires. He regularly works on long-term social-historical research projects and, in the last five years, he has been part of several solo and group exhibitions in Spain, Italy, Argentina, Andorra, Colombia and Brazil, where he exhibited his projects at different institutional and private spaces, museums, galleries, fairs and research centers.

Among his individual exhibitions we can highlight “Bauhaus 1919, modelo para armar” (2019) in Galería Siboney in Santander; “12 canciones concretas”, a project in collaboration with the musician Grösso at Rodriguez Gallery in Poznan, Poland (2018) and the Centro de Arte de Alcobendas, Madrid (2017). That same year he presented the project 155. “La balada de Simón” at La Virreina, Barcelona and “Lo Imborrable”, an intervention on the Deusto bridge in Bilbao.

Javier Diaz Guardiola, Anna María Guasch, Bea Espejo, Luis Francisco Pérez, Rosa Gutierrez Herranz, Blanca de la Torre, Óscar Alonso Molina, Osvaldo Bayer, Jaume Vidal y Jose Luis Corazón, among others, have written about his work.

Since 2007, he has been teaching at Obradoor (Taller-Laboratorio de Arte). In 2013 he founded GR, together with Rafa Castañer, an educational art project for children.

He lives and works in Barcelona since 2000.

Press

Una conexión entre dos semanas trágicas

Por El Ciudadano

02/12/2019

A 100 años de la Semana Trágica, una muestra invita a repensar la actualidad

Telam / Infobae

09/12/2019